Tail Call Elimination

Recursive functions provide elegant implementations. But they often have a risk of stack-overflow error. Tail call elimination (TCE) is a technique to address this. I first read about it in a book ‘Functional Programming in Java’ by Pierre-Yves Saumont (It is an excellent book on functional programming and I would really recommend it for every programmer. You can find the book on Amazon and Manning.) In this blog post I will discuss the what, why and how of TCE and also the support for it in Java, Scala and Kotlin.

The problem

If we have to write a recursive function for calculating factorial, we will come up an implementation like this:

public static BigInteger factorial(BigInteger n) {

return n.equals(BigInteger.ONE)

? BigInteger.ONE

: n.multiply(factorial(n.subtract(BigInteger.ONE)));

}And we can also confirm that it works well by running it for various inputs.

System.out.println(factorial(BigInteger.valueOf(5)));

// Output: 120

System.out.println(factorial(BigInteger.valueOf(10)));

// Output: 3628800Note: You can find source for this blog post at: https://github.com/balkrishnarawool/tail-call-elimination

But what if we have to calculate factorial of a big number like 50000. This is what we get by running factorial(BigInteger.valueOf(50000))

Exception in thread "main" java.lang.StackOverflowError

at java.base/java.math.BigInteger.subtract(BigInteger.java:1513)

at com.balarawool.tailcall.FactorialUtil.factorial(FactorialUtil.java:10)

at com.balarawool.tailcall.FactorialUtil.factorial(FactorialUtil.java:10)

at com.balarawool.tailcall.FactorialUtil.factorial(FactorialUtil.java:10)

at com.balarawool.tailcall.FactorialUtil.factorial(FactorialUtil.java:10)

at com.balarawool.tailcall.FactorialUtil.factorial(FactorialUtil.java:10)

at com.balarawool.tailcall.FactorialUtil.factorial(FactorialUtil.java:10)

at com.balarawool.tailcall.FactorialUtil.factorial(FactorialUtil.java:10)Note that I have removed a lot of lines from the bottom of the stack-trace.

Why does this happen? This happens because every time a function is called JVM puts the current state of the calling function on a stack and proceeds to execute the called function. When the nesting of calls is too deep, it has no memory in this stack to accommodate the calls and results in StackOverflowError. As recursive functions depend on nested function-calls, they are prone to this problem more then other functions.

Generally the stack is able to handle 5000 to 6000 nested calls. In our case we want to go 50000 and that’s a bit too much.

Tail Call

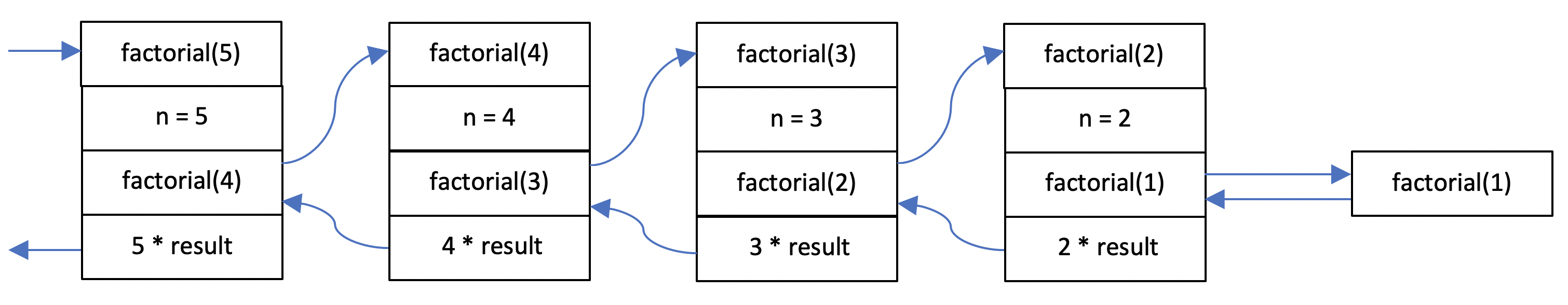

Let’s zoom in on the function-call factorial(5) a bit.

When we call factorial(5), 5 calls are made to factorial() function. As we can see in the picture above, each call calls factorial again except the last one. The last call factorial(1) returns 1 immediately. Then the series of calls unfolds. Each time a function-call gets value from the next call, it multiplies it by n and then passes the value to the caller.

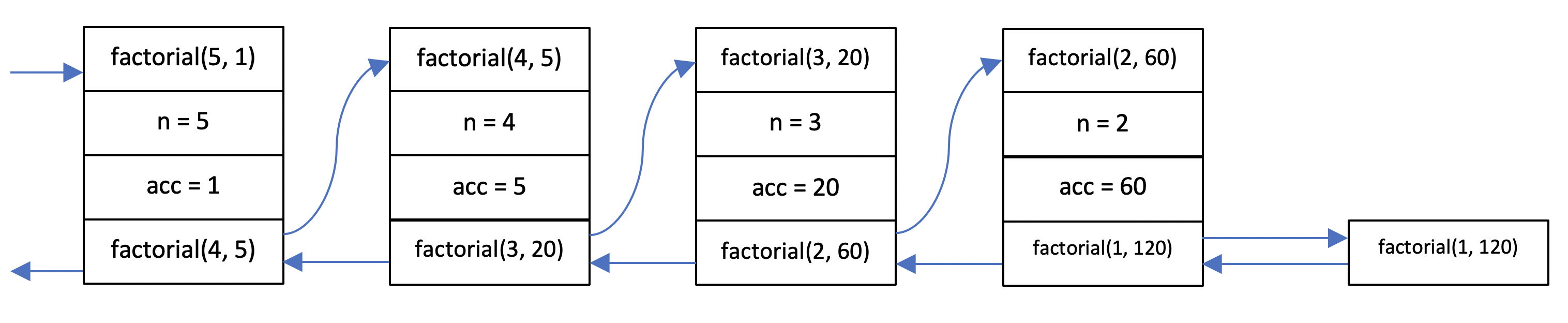

Let’s do a small modification to the function and add an accumulator. This accumulator will represent the result of intermediate multiplication so that this multiplication doesn’t have to be done after the result is received from the called function. With this change our function will look like this:

public static BigInteger factorial(BigInteger n, BigInteger acc) {

return n.equals(BigInteger.ONE)

? acc

: factorial(n.subtract(BigInteger.ONE), n.multiply(acc));

}And it can be called like this:

System.out.println(factorial(BigInteger.valueOf(5), BigInteger.ONE));

// Output: 120

System.out.println(factorial(BigInteger.valueOf(10), BigInteger.ONE));

// Output: 3628800And the picture then becomes this:

The difference between this and original function is that here, when the result of function-call is received, the function doesn’t do any more calculation it simply returns that result. This means the recursive function-call is the last thing the function does before returning. Such a recursive call is called tail-call and such recursive function is said to be tail-recursive.

For tail-recursive functions, it is not necessary to maintain their state on stack. Instead we can simply return the result of function called by it to the function calling it. So if we represent the tail-recursive functions with a data structure that eliminates the need to save state on stack, we can solve the problem of StackOverflowError.

Tail Call Elimination

Let’s see how we can create that data structure. Let’s call this TailCall.

If we look at the picture from above again, we see that there are two kinds of function-calls: intermediate and terminal. Intermediate calls call the function again but terminal call returns immediately. We will represent intermediate calls by a class called Suspend and terminal calls by a class called Return. The intermediate calls will need the ability to hold result of future calls. This can done by using Supplier.

public abstract class TailCall<T> {

public abstract boolean isSuspend();

public static class Return<T> extends TailCall<T> {

private T value;

private Return(T value) {

this.value = value;

}

@Override

public boolean isSuspend() {

return false;

}

}

public static class Suspend<T> extends TailCall<T> {

private Supplier<TailCall<T>> supplier;

private Suspend(Supplier<TailCall<T>> supplier) {

this.supplier = supplier;

}

@Override

public boolean isSuspend() {

return true;

}

}

}Let’s add a method eval() that calculates the final result. And then add a method resume() to step through the intermediate calls. resume() would be useful during evaluation. It only makes sense for Suspend. For Return, it will throw an exception. So the complete class looks like this:

public abstract class TailCall<T> {

public abstract boolean isSuspend();

public abstract T eval();

public abstract TailCall<T> resume();

public static class Return<T> extends TailCall<T> {

private T value;

private Return(T value) {

this.value = value;

}

@Override

public boolean isSuspend() {

return false;

}

@Override

public T eval() {

return value;

}

@Override

public TailCall<T> resume() {

throw new IllegalStateException("resume() called on Return");

}

}

public static class Suspend<T> extends TailCall<T> {

private Supplier<TailCall<T>> supplier;

private Suspend(Supplier<TailCall<T>> supplier) {

this.supplier = supplier;

}

@Override

public boolean isSuspend() {

return true;

}

@Override

public T eval() {

TailCall<T> tc = supplier.get();

while(tc.isSuspend()) {

tc = tc.resume();

}

return tc.eval();

}

@Override

public TailCall<T> resume() {

return supplier.get();

}

}

}Stack-safe recursive functions

Before we write stack-safe version of factorial() function, let’s add couple of convenience methods to TailCall: ret() and sus(). These would help us create Return and Suspend objects respectively.

public static <T> Return<T> ret(T value) {

return new Return<>(value);

}

public static <T> Suspend<T> suspend(Supplier<TailCall<T>> supplier) {

return new Suspend<>(supplier);

}And now we can write the stack-safe version of factorial using TailCall.

public static BigInteger factorialStackSafe(BigInteger n) {

return factorial_(n, BigInteger.ONE).eval();

}

private static TailCall<BigInteger> factorial_(BigInteger n, BigInteger acc) {

return n.equals(BigInteger.ONE)

? ret(acc)

: sus(() -> factorial_(n.subtract(BigInteger.ONE), n.multiply(acc)));

}And finally we can find factorial of 50000 with:

System.out.println(factorialStackSafe(BigInteger.valueOf(50000)));It is such a big number, it doesn’t make sense to add the literal value here. But you can find it here.

So in general, if you want to avoid stack-overflow error for recursive functions do this: First convert it into tail-recursive function and then use TailCall API to make it stack-safe.

Tail Call Optimization

Tail Call Elimination (TCE) is sometimes referred to as Tail Call Optimization (TCO). In fact, it is an optimization. But as Pierre-Yves points out in his book Functional Programming in Java that when dealing with functional programs, there are so many recursive functions and nested/composed function-calls are involved that this technique becomes a necessity and no more remains an optimization. So Tail Call Elimination is a better term.

Tail recursion support in Kotlin and Scala

As we saw so far, Java does not provide support Tail Call Elimination out-of-the-box, but it can be easily added with the TailCall API. However Kotlin and Scala do provide that. So there is no need for creating and using a TailCall class.

Kotlin equivalent of the factorial function would be:

fun factorial(n: BigInteger, acc: BigInteger): BigInteger {

return if (n == BigInteger.ONE) acc

else factorial(n - BigInteger.ONE, n * acc)

}This can be used to calculate factorials of 5 and 10 like this:

println(factorial(BigInteger.valueOf(5), BigInteger.ONE))

// Output: 120

println(factorial(BigInteger.valueOf(10), BigInteger.ONE))

// Output: 3628800But for println(factorial(BigInteger.valueOf(50000), BigInteger.ONE)) this gives:

Exception in thread "main" java.lang.StackOverflowError

at java.base/java.math.BigInteger.multiply(BigInteger.java:1593)

at java.base/java.math.BigInteger.multiply(BigInteger.java:1564)

at com.balarawool.tailcall.FactorialUtilKtKt.factorial(FactorialUtilKt.kt:7)

at com.balarawool.tailcall.FactorialUtilKtKt.factorial(FactorialUtilKt.kt:7)

at com.balarawool.tailcall.FactorialUtilKtKt.factorial(FactorialUtilKt.kt:7)

at com.balarawool.tailcall.FactorialUtilKtKt.factorial(FactorialUtilKt.kt:7)Note that a lot of lines from the bottom of the stack trace are removed.

To make Kotlin aware that this is a tail recursive function, we just have to add tailrec in front of the function definition.

tailrec fun factorial(n: BigInteger, acc: BigInteger): BigInteger {

return if (n == BigInteger.ONE) acc

else factorial(n - BigInteger.ONE, n * acc)

}This can be then used to calculate factorial of 50000.

Scala equivalent of the factorial function would be:

def factorial(n: BigInt, acc: BigInt): BigInt =

if (n == 1) acc

else factorial(n - 1, n * acc)This just works perfectly for 5, 10 and 50000. There is no need to tell the compiler it is a tail-recursive function as the compiler figures that out by itself.

println(factorial(5, 1))

// Output: 120

println(factorial(10, 1))

// Output: 3628800

println(factorial(50000, 1))

// Outputs a big big numberHopefully this has given you a good idea about what Tail Call Elimination is, why is it needed and how to achieve that in Java, Scala and Kotlin.

The source code for this post can be found here: https://github.com/balkrishnarawool/tail-call-elimination